Crime in Nashville isn't at an "all-time high"

Late in the DA race, Myers reaches for outdated, inaccurate talking points.

…a data-driven short-read in which Nicole weighs in on Sara Beth Myers’ questionable campaign messaging, wins a Twitter argument, and is right.

Full disclosure: I (Nicole) have publicly endorsed P. Danielle Nellis in the race, due in no small part to what I’ll be discussing in this piece.

Tomorrow is the last day to vote in this year’s Democratic primary for district attorney.

There are some things we need to talk about.

There’s plenty of coverage out there about the candidates, but what I want to focus on is a strategy being employed by candidate Sara Beth Myers. It boils down to, “Crime is skyrocketing, and incumbent DA Glenn Funk is not doing a damn thing to keep you safe.”

This message centers on a common refrain advanced by local media and elected officials trying to scare us into giving the police more tools and more money every year. If you fully buy what’s being sold, you’d probably never leave your home for fear of being brutally assaulted. Because, they say, crime is at an “all-time high” in Nashville. (See, for example, Myers’ husband melting down on Twitter over my criticism of his wife’s TV ad.)

There’s a problem with the message: it’s not true. It’s not even close to being true. How do I know this? I looked at the data.

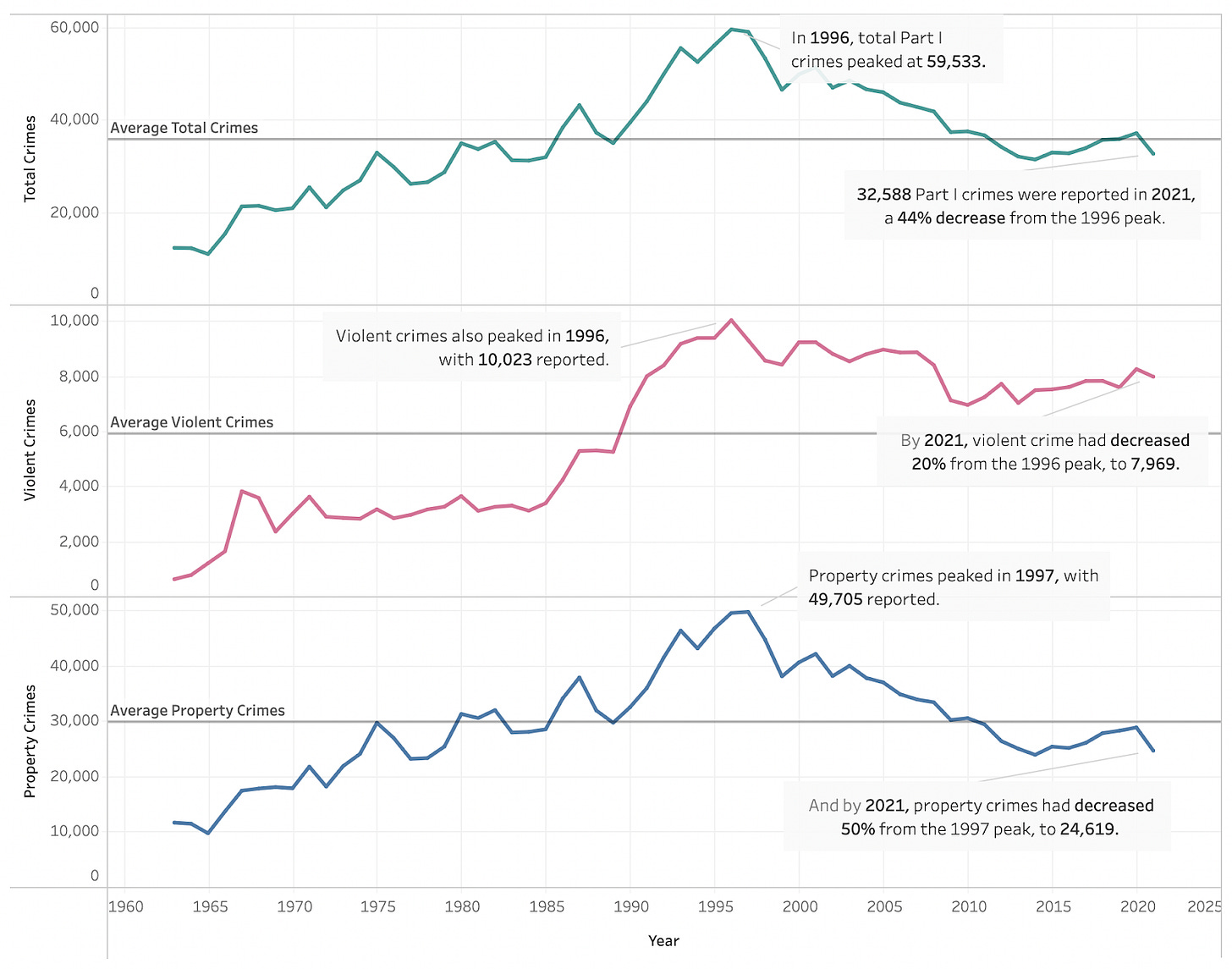

Since 1963, when the Nashville city government and Davidson County government were consolidated, the Metro Nashville Police Department has annually reported a subset of crimes known as “Part I crimes” to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) database. Part I crimes include the serious crimes people are most likely to report and that you hear the most about in the media – violent crimes (aggravated assault, rape, robbery, and murder) and property crimes (burglary, larceny, and auto theft).

MNPD’s public reporting currently only includes data through 2020, but the FBI’s database contains the data from 2021. Since population estimates fluctuate, the rate per 100,000 residents isn’t exact, but taken together with the decrease in number of Part I crimes committed from 2020 to 2021, it’s clear that crime is falling in Nashville. (Note: while rate is a better comparative measure because it takes population growth into account, I chose to focus on crime count in my chart, mostly to demonstrate just how ridiculous this argument about rising crime is. If you hover over any particular year, you can see the rate.)

As you can see, crime not at an all-time high. It’s actually quite low when compared to the peak crime rate in the mid-1990s. Yes, there was an increase in crime from 2019 to 2020 in Nashville, just as there was in basically the entire country. 2020 was a weird year, as you may recall. But by no means is crime skyrocketing in Nashville.

Now, I don’t want to downplay the impact that crime has on the individuals who fall victim to it. And I’m not suggesting that it’s a good thing that we saw an uptick in both property crimes and violent crimes in 2020, compared to 2019. I think we can all agree, less crime is good.

What I am attempting to do here, though, is to level-set. If we’re going to talk about crime and develop strategies to address crime – which we definitely should be doing – we should at least be operating from a set of facts, not feelings.

Feelings matter, don’t get me wrong, but if we rely on them too heavily, we end up with public policy that doesn’t actually solve the problem. We run the risk of devoting resources to strategies that won’t work. Because where do you think we put our money when we buy into this crime wave propaganda? We put it into the police. We equip them with more tools, more surveillance, more power.

Instead of investing in community-based strategies to address the root causes of crime – like poverty, housing instability, lack of social supports – we beef up our ability to respond to it after the fact. We invest in downstream strategies at the expense of upstream solutions. We become reactive.

So, what do you do if you’re a candidate who keeps hearing from residents that they’re concerned about the crime rate? Well, you’ve got a couple of options:

You could educate the electorate, setting the narrative straight and explaining our current situation in the context of historical trends, or

You could lean into that fear and attempt to capitalize on it to further your aims and get more votes.

Sara Beth Myers appears to have chosen the latter option. It’s a choice, and it’s hers to make, but it’s not one I can respect from someone who’s running for one of the most powerful offices in the city. Her willingness to advance a blatantly false narrative on the campaign trail reflects a fundamental dishonesty and inability to challenge the status quo. That’s not someone I want as my district attorney.

Note: Rhetoric about rising crime rates has historically been used to explicitly engender fear of people of color, most often Black men. Perhaps the most infamous example of this is the William Horton ad that aired during the 1988 presidential campaign. That’s a topic for a different piece, and I’m certainly not equating Sara Beth Myers to George H.W. Bush, but it’s worth placing ads and rhetoric like this in context.